The Worcester Family

A missionary family that made an exceptional commitment, the Worcesters are remembered kindly and often by history. Rev. Worcester and one of his daughters, Ann Eliza, were prominent translators of the Bible into the Cherokee and Creek languages. Many family members saved letters which comprise a substantial archive at the McFarlin Library, University of Tulsa. Their lives and fates were enmeshed with Cherokee history through a lifetime of service in Park Hill, Indian Territory. One of Worcester’s granddaughters, Alice Robertson, served as Oklahoma’s first woman in Congress from 1921 to 1923. An excellent chronicle of Rev. Worcester’s amazing life is Althea Bass’s 1936 biography, Cherokee Messenger.

After she was hired by the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions, Hattie Sheldon lived at the Park Hill mission where she taught under Worcester’s supervision. She became very close with the Worcester family. In the 1904 book, Home Mission Heroes: A Series of Sketches, it is written that Hattie “was much like a daughter in the family.” (Home Mission Heroes, The Trow Press, New York, Copyright 1904 by The Board of Home Missions of the Presbyterian Church in the USA, reproduced by Google books and available at the Harvard Book Store).

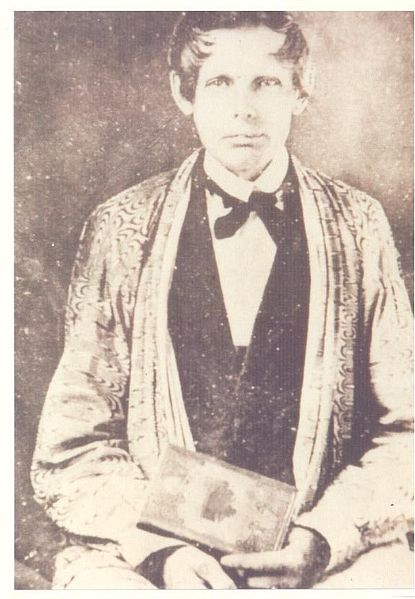

REV. SAMUEL AUSTIN WORCESTER

A towering character who figures prominently into Cherokee history in the 19th century, as well as Georgia state history, Rev. Worcester makes his first appearance late in A Distant Call: The Fateful Choices of Hattie Sheldon. The novel portrays the fact that his life’s work centered upon service to the Cherokees, whom he loved deeply. His employer was the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions, a Boston based society.

His singleness of purpose to the Cherokees in Indian Territory kept him away from his old home in New England for over thirty years. Several sources confirm that he finally made a long overdue visit there in 1856. Because Hattie Sheldon was then a young woman in Utica, NY, the story lent itself to a convergence of their paths during that journey. She was hired and worked very closely with Rev. Worcester as perhaps the last school teacher hired at the Park Hill Mission.

Rev. Samuel Austin Worcester (1798-1859)

Rev. Samuel Austin Worcester (1798-1859)

- http://digital.library.okstate.edu/encyclopedia/entries/w/w0020.html

- http://www.aboutnorthgeorgia.com/ang/Samuel_Austin_Worcester

- http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Samuel_Worcester

- http://www.georgiaencyclopedia.org/articles/government-politics/worcester-v-georgia-1832

Rev. Worcester’s own letters, kept in a voluminous archive at Harvard University in Cambridge, MA, reveal a man of enduring patience, devotion and character. Educated in linguistics as well as theology, he took up the printing trade, as well. Employing Sequoyah’s new Cherokee alphabet with the aid of Eastern educated Cherokee scholars, Worcester began to translate the Bible into Cherokee. He started this work when the Cherokees still lived on their ancestral lands in the southeastern United States. After gold was discovered in Georgia, the state coveted the land and restricted white missionaries as a means to gain control. When Worcester disobeyed and refused to pledge allegiance to Georgia, he was imprisoned at hard labor.

A family man, Rev. Worcester was the father of six children. His wife died following the birth of his sixth child, Mary Eleanor, only three years after arriving in the new Indian Territory. Shortly, he remarried a single woman missionary at another mission station near his own Park Hill Mission. Besides his second wife, Erminia and youngest daughter, Mary Eleanor, the rest of his family does not appear prominently until the second book in the series.

ERMINIA NASH WORCESTER

Rev. Worcester’s second wife, thirty nine year old Erminia Nash, had served as a missionary at the Dwight Mission down the road from Park Hill. A pastor’s daughter and native of Cummington, MA, she had joined the Cherokee mission in 1825, at age 24, as a teacher. Because of her active energy in her work, the Indians gave her a nickname from their own language, “Outrunner,” or “One who outruns another.” She married Rev. Worcester in April 1841 and immediately took up the challenge of caring for Ann Eliza (14), Sarah (12), Hannah (7), Leonard (5), John Orr (3), and Mary Eleanor (11 months).

In her prominent 1936 volume, Cherokee Messenger, Althea Bass described Erminia in terms of her letters, which survive her today in several archives. They were “slightly untidy, slightly dull, and slightly self-centered” according to Bass. Letters and mentions from the children and grandchildren further revealed difficulties with Erminia, but she was loyal and remained close to Worcester’s children throughout her life. She escaped the dangers of the Civil War for several years, only to return to live in the devastated Indian Territory after its end. She died at the age of seventy on May 5, 1872. Her grave in Park Hill, Oklahoma lies at the foot of her husband’s grave at a perpendicular angle. She had specified that she felt unworthy to be buried beside him.

MARY ELEANOR WORCESTER

Unlike her siblings, Mary Eleanor never enjoyed the care of her birth mother who died hours after she was born. The only mother she ever knew was her stepmother, Erminia. Numerous references reveal that Mary Eleanor was a more excitable personality and the subject of her family’s concern during her youth. Family letters reveal that she suffered with “melancholia,” which led her father to seek medical care for her back east. She recovered and was educated there, returning to Indian Territory after her father’s death. While teaching in Arkansas, she married a secessionist surgeon in Confederate service, which caused tension among her Union family. Her second husband was Mason Fitch Williams, MD. They had two sons.

American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions

The first foreign missionary organization in America, the American Board was formed in 1810. It sent missionaries around the world. This occurred as a result of of the Second Great Awakening in America. Rev. Worcester’s uncle was an early president and organizer of the society, which was largely made up of Congregationalists. Indian tribes within the United States were considered foreign, which brought them under the aegis of the society. It’s archives at Harvard University serve today as an important sociological research source for scores of cultures because missionaries wrote detailed reports back to the society’s headquarters in Boston for well over 100 years.

- American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions, the first successful foreign mission society in the United States:

http://www.cherokeephoenix.org/Article/Index/6541 - http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/American_Board_of_Commissioners_for_Foreign_Missions